I’d Rather Talk About Indices Than Tariffs

Ask A CIO #40

It’s been an eventful 24 hours. As investors, it’s messy out there.

There’s not much consensus on anything at the moment, except that we seem to be caught in a game in which everyone gets to lose, just to varying degrees. Even the market’s favorite pastime, guessing ‘what will Jerome Powell do?’, is more contentious than usual. Some Wall Street economists are predicting zero Fed rate cuts, while others have suggested up to five (in the event of a recession). Maybe they all should have just sent a note with the shrugging emoji.

In these moments of high volatility and uncertainty, there is value in slowing down, in making deliberate decisions. And of course, as long-time investors can appreciate, there is value in diversification.

Moving away from macroeconomic unknowns, this week’s question raises the question of why there are so many equity indexes, and how to choose from among them.

I remember when Tesla joined the S&P 500 and Charles Schwab (the man, not the brokerage) wrote investors a letter touting the Schwab 1000 index and how Tesla had been included for several years before it joined the S&P 500, and investors who owned the index had excellent returns for that reason.

What is the rationale for choosing the S&P 500 versus a broader equity index, or another equity index with a tilt like momentum or growth?

I appreciate this question. First, you alerted me to the existence of the Schwab 1000 Index. I quickly perused the background, and it looks like Charles Schwab created the Schwab 1000 in 1991 as their own proprietary index, representing the largest 1,000 U.S. stocks.1

Second, I rarely get the chance to talk about indexes. And investors really should talk about them more often! At a minimum, they serve as benchmarks for how we think about investment success. And in many instances, they also serve as the basis for how we invest.

So what makes for a good index? Generally speaking, an index should be representative, transparent, and investable. The index’s methodology should define the universe of permissible holdings and additional screening criteria.2 Beyond these basics, judging indexes gets a lot more subjective.

Different investors care about different things. Similarly, fund managers have a wide range of investment mandates. The end result of these various demands has been a proliferation of indexes (which, to be clear, I don’t necessarily think is a great outcome).3

But back to your question – why is the S&P 500 Index so commonly chosen as the default reference index for the U.S. equity market?

I’ll give the predictable answer first. The S&P 500 more or less covers the largest publicly traded companies across the U.S. economy. It is broadly diversified and representative of companies across industries. The index has been around since 1957.

There’s also value in the ubiquity of the S&P 500. Many investors use the S&P 500 Index, because many investors use the S&P 500 Index. And there is value in having a common reference point.

Yet despite the S&P 500 Index being a widely followed and widely referenced benchmark, it remains challenging to beat. Without getting into another discussion on active versus passive, or debating the structural impact of the rise of passive investing, I’ll simply say this – the performance success of the S&P 500 index suggests that it is a fairly comprehensive representation of the U.S. equity market.4

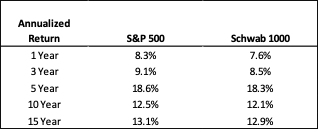

To illustrate this point, and bring it back to your original question, the following is the performance of the S&P 500 Index as compared to the Schwab 1000 Index for multiple time periods ending March 31, 2025. If the Schwab 1000 Index were just another equity manager, it too underperforms the S&P 500 Index.5

Interestingly enough (acknowledging that interesting is also subjective), the S&P 500 Index is not fully rules-based and includes a fair amount of subjectivity. Companies are chosen by a committee at S&P Dow Jones. The committee actively selects companies based on market capitalization, liquidity, profitability, and industry representation.6

One of the consequences of the S&P 500 selection methodology is that a company might not be included in the index even if it is one of the largest 500 companies in the U.S. equity market. As I noted above, profitability is a key criterion. Now you can see how a large tech company, growing but not yet profitable, would be excluded.

In contrast, the Russell indexes, another set of commonly used U.S. equity indexes, are fully rules-based.7 My quick review of the Schwab 1000 suggests that it too is rules-based.8 It therefore makes sense that Tesla was included in the Russell and Schwab indexes before making its way into the S&P 500 Index.

Finally, regarding your suggestion to consider a broader index, or an index with a factor tilt (e.g., growth, value, momentum, etc.) – each of those choices introduces a different risk. A broader index likely introduces smaller capitalization companies. An index with a factor tilt reflects a bet on that factor. It’s not a perfect answer, but I think of the S&P 500 as being like a neutral position on the U.S. stock market.

Thanks for the question! As always, feel free to reach out: askacio@ivyinvest.co.

See you in two weeks,

Wendy

Investment Company Institute: Indexes and How Funds and Advisers Use Them: A Primer

Being an index provider is a lucrative business! Talk about sticky, recurring revenue. And if I had to guess, the cost of paying index providers probably contributed to Schwab’s decision to start their own. For your reference, the largest index providers out there are FTSE Russell, MSCI, and S&P Dow Jones.

I would compare the challenge of outperforming the S&P 500 with the challenge of outperforming other international market indexes. It has historically been challenging for active equity managers to beat the S&P 500 Index. In other international equity markets, active equity managers have shown greater ability to outperform the most common country indexes, suggesting those indexes may not be as representative of those markets.

Source: Bloomberg

This family of indexes includes the Russell 3000 (arguably the most commonly used U.S. all-cap equity index), the Russell 2000 (definitely the most commonly used U.S. small-cap equity index), and the Russell 1000, along with a multitude of value, growth, and other size versions.