Comparing J-Curves

Ask A CIO #50

I’m writing this week from Dallas, where FIN News is celebrating its 20th anniversary as a media company (congrats!) and hosting its inaugural emerging manager conference. I would encourage emerging managers and fellow LPs to put it on your radar for future years!

While prepping for a panel discussion on ways that emerging managers can engage with potential nonprofit LPs, the conversation turned briefly to the challenges faced by diverse emerging managers. There was a time when diverse emerging managers were a hot topic. Whether sincerely or performatively, LPs and GPs would actively discuss the ways in which the industry could better support these managers. It wasn’t really that long ago, but it certainly feels like it was a different era.

Where do things stand today? As far as I can tell, the individuals and LPs that cared about expanding the GP universe before it was trendy, still do. And bluntly, the ones that didn’t, never did. The landscape may look and feel changed, but silver lining, I think the signals from LPs on this front are now arguably clearer and more reliable.

On to this week’s question:

Why would LPs care about the J-curve of different private strategies? I keep seeing it in managers' decks and I just don't understand why it matters for illiquid strategies. Either way, someone has to manage liquidity, accounting for capital call uncertainty and deployment period.

It’s a good question, and you’re right. Institutional LPs increasingly care about the J-curve. Somewhere along the way, J-curves shifted from being more of an academic consideration to being one more factor in how GPs are evaluated.

Before we go further, I’ll quickly explain the J-curve for those who might be less familiar. Outside of private market investing and maybe parts of economic theory, it’s not exactly a commonly referenced term.

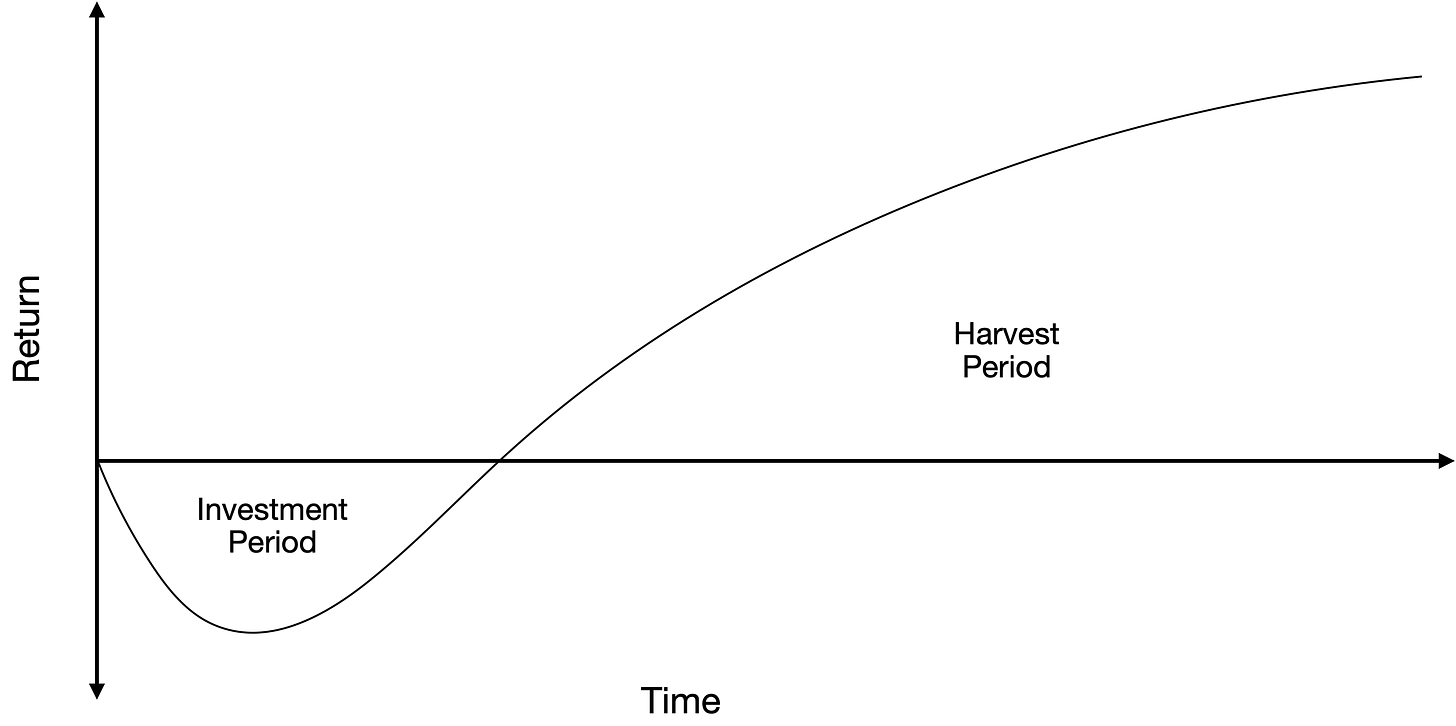

In the most basic sense, the term J-curve literally describes the shape of a curve that is graphed from a set of data points. Typically, the y-axis represents whatever value is being measured, and the x-axis references the passage of time. Conceptually, something that experiences a J-curve is something that experiences negative values for a time before eventually experiencing positive value.

As it specifically pertains to private market funds, J-curves help describe how investors experience the performance of drawdown funds. I’ve written before about the mechanics of private market investing through drawdown structures, where investors are subject to a period of capital calls at the outset of each investment. During this period, investors also typically experience negative returns, as funds accrue fees and expenses but fund investments (e.g., private companies acquired by a buyout firm) have not yet had time to generate value. Eventually, the expectation over time is that the investments do increase in value, and the private fund performance turns positive, ideally meaningfully so. The chart below provides a generic visualization of this J-curve pattern.

Turning back to the question – why do LPs care about the J-curve? Particularly if, as long-term investors, the eventual total returns of funds are presumably far more important.

Well, I think there are a few reasons, some admittedly more straightforward than others. Let’s start with the ones that are probably easiest to appreciate.

When investors talk about variations in J-curves, they’re typically focusing on differences in the duration of that negative return period and/or the depth of the negative return (temporarily) experienced. All else equal, a shorter J-curve is better than a longer one, and a shallower J-curve is better than a deeper one. I think the rationale here is fairly apparent – getting to a positive return more quickly is generally preferable.

Of course, all else is usually not equal, but you get the idea. For two different strategies that generate similar total returns, the path for either set of returns can serve as a meaningful differentiator.

Another situation where differences in J-curves are more readily tangible: nascent private investment programs. In a mature private investment program, the portfolio as a whole is past the J-curve. Any new commitment might incrementally generate negative returns but probably won’t send the return profile of the total private program back into negative territory.

A private investment program still under development, however, might be going through a portfolio level J-curve, with the aggregate private portfolio reflecting negative returns for a time. I imagine that LP is likely to care a lot about the expected return paths for incremental new commitments.1

Moving on now to use cases where reasonable minds might differ on the merits.

For some managers and strategies, touting shorter and shallower J-curves has become an effective marketing point. In a world where total returns are judged in a vacuum, strategies that can achieve positive returns more quickly but might ultimately generate lower total expected returns will have difficulty competing against strategies that might have prolonged initial periods of negative returns but higher total expected returns. Think private credit versus venture capital, for instance.

But since LPs generally don’t judge returns in a vacuum, it often does in fact matter how a strategy’s return profile fits into the context of the LP’s overall portfolio. Especially these days, where liquidity is often top of mind. A manager with a lower expected total return might instead point to faster distributions as an offsetting advantage.

Finally, some LP compensation structures effectively reward LPs for caring about the J-curve. There are wide variations in how institutional LPs are paid and incentivized. A not insignificant portion of institutional LPs focused on private markets are compensated based on their private portfolio performance as measured by internal rates of return (IRR). Under these circumstances, shallower and shorter J-curves (along with tactics used to improve J-curves) are generally preferable.2

When I decided to take on your question, I didn’t think I had that much to say about J-curves. For better or worse, I apparently do.

I guess all that’s left to say is, thanks for making it to the end of this fairly dry discussion! As always, reach out with questions: askacio@ivyinvest.co.

See you in two weeks,

Wendy

If you enjoyed this post, you might also enjoy the Ivy Invest app!

Click below to create an account and learn more about our endowment-style fund:

There are potential impacts on dollars available for institutional operations, particularly for endowments and foundations where spending policies are indexed to total portfolio values.

It’s one reason the proliferation of capital call lines of credit was so contentious for so long. Some LPs liked the resulting higher IRRs while others were displeased with incurring extra borrowing costs.